–

On the afternoon of 25th July 1983, 35 Tamil prisoners held under the PTA or Emergency Regulations were massacred in a prison riot. What was more remarkable was the second attack on the surviving prisoners two days later, killing another 18 prisoners after strong protests from abroad and measures had apparently been taken to protect the survivors.

Both massacres were documented in the UTHR(J) publication Sri Lanka: The Arrogance of Power; Myths, Decadence and Murder[1]. It adduced strong reasons pointing to a section of the government of the day as prime mover in the crime supported by some members of the prison staff. Among the latter it identified Jailor Rogers Jayasekere a supporter of the ruling UNP from Kelaniya, the former electorate of J.R. Jayewardene, who was then president. The old Kelaniya electorate was in 1983 represented by Ranil Wickremasinghe (Biyagama) and Cyril Mathew (Kelaniya), who were both instrumental in the July 1983 communal violence, particularly the latter.

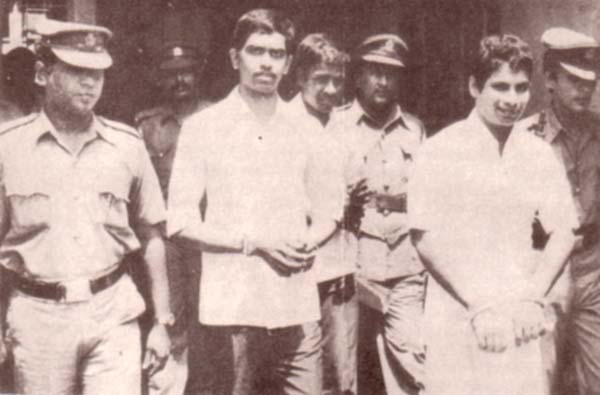

N. Thangathurai and Kuttimani Yogachandran amidst prison guards

An army contingent stationed at the prison had a direct radio link to Army HQ, where during both prison attacks the Security Council was meeting with President Jayewardene himself present. We are clear that the Army unit at the prison was ordered not to intervene and on the first occasion, Lt. Mahinda Hathurusinghe further prevented the injured prisoners being removed to hospital and ensured that they were killed or died through neglect or suffocation after being piled one on top of another.

Arrogance of Power points to political interference in the inquest proceedings. The Government had armed itself with enough draconian powers to dispose of the bodies without an inquest, although the bodies having been taken to the Hospital mortuary created a problem. Because of international interest Secretary/ Justice, Mervyn Wijesinghe, persuaded the Government to hold inquests in both instances. To this end the reluctant Colombo Magistrate Keerthi Wijewardene was told by Wijesinghe to hold the inquests. The inquest verdicts, while routinely admitting homicide and calling upon the Police to conduct further investigations were also crafted to rule out state complicity and culpability. They long remained the Government’s defence and the last official word on the subject.

The supplementary information here comes from two sources. One is Lalanath de Silva, the son of Alexis Leo de Silva, then Superintendent of Welikade Prison who passed away in 1995. The other is Nuvolari Seneviratne who was the Lieutenant in charge of the army unit outside Welikade Prison during the second massacre on the 27th. But first a note on the ‘Truth’ Commission.

Judicial Censorship of SP Leo de Silva

In July 2001, President Kumaratunge appointed the Presidential ‘Truth’ Commission on Ethnic Violence headed by former Chief Justice Suppiah Sharvananda, with S.S. Sahabandu and M.M. Zuhair as additional members. It was mandated to inquire into the nature, causes and the extent of gross violations of human rights and destruction property in violence between January 1981 and December 1984. With regard to the violence of July 1983, Suriya Wickremasinghe, who had done extensive work on the prison massacres, appeared before the Commission. We give below in her own words her assessment of what was achieved and what it failed to achieve on the question of the massacres:

“Where the Welikade massacres were concerned for instance it did hardly any – if any – investigation of its own. It relied on me (CRM) for practically everything (for instance, even the inquest proceedings were supplied to it by us) and seemed more than happy with just our material. What it should have done is taken our material as a starting point and then followed up from there, with all its powers of investigation and summoning witnesses, which we didn’t have. For instance it could and should have tried to obtain the statements recorded by the police after the 1st massacre. The instructing attorneys in the 35 civil cases filed by dependents of victims (assisted by CRM; it was in pursuance of these that we tracked down and interviewed survivors) called for these time and again in preparation for the trials, but were met with evasion after evasion by the Police. The cases never came to trial because they were eventually settled, state paying some compensation but without admitting liability.

“By the time of the ‘Truth’ Commission, I guess I was exhausted with putting the facts before them and it was probably partly my fault I did not press sufficiently for follow-up, or possibly I thought it would be no use. Welikade was only a small part of the Commission’s whole remit. In its report the Commission did pay CRM and me a handsome tribute, which was certainly gratifying, but we had really hoped that it would investigate further and uncover information which we had not already found out for ourselves.”

When contacted by us Lalanath de Silva told us: “My evidence before the Truth Commission was essentially about what I knew – things I heard and saw for myself – and things my father told me or discussed with me. In July 1983 I was a young lawyer having been admitted to the bar in August 1982. My father discussed many legal and other matters related to his duties and this incident with me.

“If there was one thing he was ever so clear about – it was his duty as a Prison official with respect to all in his custody – namely that under the law they were committed to “safe custody” and that it was his bounden duty to keep them safe and well until they received due process. That is why the Magistrate at the first inquest refused to record his full story – abridged what he said, taking down only what he wanted. At one point my father refused to continue unless his evidence was accurately recorded.” The Magistrate became angry andstopped taking any more evidence from my father.

“In any event, my father told me that the AG’s department counsel called my father outside the room where the inquest was being held and had attempted to persuade my father to go along – his plea was that the truth would place Sri Lanka in a very adverse position internationally. My father refused to cooperate. He wanted it recorded that the Army had been complicit (by commission and omission) in the whole affair, that there were prisoners still alive after the massacre that he wanted sent immediately to the accident service for emergency treatment and that the army had blocked this and that his pleas to higher authorities to move the Tamil detainees away from Welikade even before the massacres had fallen on deaf ears. Of course none of this was recorded!”

“At the second inquest, he did not take my father’s evidence because he knew my father insisted on speaking the truth and instead selected some junior officers. It was clear to my father that both the AGs department personnel and the Magistrate had one clear objective – to cover up the incident and return a finding where no one could be identified and prosecuted for the massacre. My father paid for his stance.”

This clarifies the observation made by Suriya Wickremasinghe of the Civil Rights Movement who closely followed this case from the very outset. She observed the lack of continuity in Leo de Silva’s testimony as recorded in the first inquest report and felt that parts of it were missing.

The Magistrate entered a verdict of homicide, from a ‘general state of unrest’ among 800 prisoners housed upstairs in the Chapel Section, ‘which had ended up as a riot’. He further concluded that, “None of the prison officers or the army officers summoned thereafter could have done anything under the circumstances to prevent the attack. They have all been completely overpowered.”

The 2nd Massacre 27th July

Most people, especially Tamils, assumed that the first massacre was planned and executed on behalf of the government of the day and the second followed because the job was incomplete, with about half the PTA detainees remaining alive. Suriya Wickremasinghe, who more than anyone else has painstakingly studied the matter from the start, and tracked down and interviewed most of the survivors in different parts of the world, adds a note of caution. While she formed a strong impression that the second massacre became imperative to cover up the first, she feels the first massacre was not necessarily pre-planned at high level. Her reasoning is that following the inquest into the first massacre, the Magistrate had issued routine instructions to the Police to carry out investigations and the Police did question the survivors and start recording statements which contained some damning testimony. The survivors had become witnesses to the crime. We will return to the question of premeditation towards the end.

Suriya Wickremasinghe added, “Some survivors were circumspect and didn’t say much. Others came out with names – e.g. Manickathasan (of the PLOTE who was killed by the LTTE in 1999), told me he named two jailors. He said their names were written down in inverted commas in his statement. Prison staff were listening while his statement was recorded and one of them, a thin jailor whose name he did not know, advised him not so mention these two names, otherwise the people here will do the same to you. He also told the police when asked that he could identify the two convicted prisoners who had broken down through the ceiling and come into their corridor…. …This would explain why, if indeed it happened, it was felt necessary to import criminals from outside – Lt. Seneviratne’s testimony below – for the second occasion, to make sure the job was properly done.”

While some survivors felt safe after being moved to the Youthful Offenders Block, others felt that they were in even greater danger than ever because they were witnesses. They would not be allowed to live but they would die fighting. Suriya adds, “Therefore they started preparations to defend themselves – improvised weapons by twisting tin plates to form missiles, collected urine and chillie water from their gravy in their buckets, got ready to entwine their canvas sleeping-sheets round the iron bars to hold the cell doors closed. That is why they were able to fight back and why some of them managed to survive.”

During the morning the Chief Jailor informed Acting Commissioner of Prisons C.T. (Cutty) Jansz that another attack on the surviving Tamil PTA prisoners was imminent. (At the inquest, he also added plans for a mass jailbreak to the impending attack on PTA prisoners, which we now have good reason to believe, was prompted into the testimony by the AG’s Dept.) Jansz contacted Mervyn Wijesinghe, Secretary/ Justice and wanted moves to fly the surviving prisoners out of Colombo, as had been agreed after the first attack, expedited. For this purpose Jansz attended the Security Council meeting at Army HQ that afternoon.

We make some remarks about the layout that are necessary for the account below. The prison has an outer perimeter wall. At the entrance there is an arch fitted with a solid door with a small door built into it to admit visitors. The larger door is opened for vehicles. Inside one is in a covered way, a kind of tunnel. On either side of the tunnel are office rooms and visitors rooms. At the end of the tunnel is a second gate made of metal bars through which one could see into the prison compound. A public coin-operated telephone was on a side of this tunnel. The standard security procedure for vehicles entering the prison is that when they go in through the first door, that door has to be closed and secured before the other is opened.

Lt. Nuvolari Seneviratne of the Field Engineering Unit led the platoon that was on duty outside the prison. His unit had arrived in the night following the first massacre and, at midnight, he took over duties at the prison from Lt. Hathurusinghe of Artillery. The latter left in the morning. Some of Seneviratne’s men were at the guardroom at the prison entrance. Lt. Seneviratne told us that the duty of the soldiers at the entrance was to check the papers of the vehicles coming into the prison and ensure that they were government vehicles. The identity checks were the work of the jail guards just inside the entrance. The soldiers communicated freely with the jail guards and passed on to him news of what was going on inside. The soldiers at the entrance told him that they heard from the jail guards that some of the official vehicles coming in were bringing in underworld figures. They did not go back out in the vehicles that had brought them.

Asked who the underworld figures were, Seneviratne replied, “I did not see them myself and there is no way my men would have known them. But the jail guards knew them as persons who had been in and out of jail. They told my men.” Through sensing the atmosphere and what his men learnt from the jail guards, Seneviratne confirms that plans to attack the Tamil PTA detainees were widely known in the morning. Jansz had acted on this, yet nothing was done to ensure security of the prisoners.

Lt. Seneviratne did not communicate the prospect of an attack to Army HQ. He says that his men were well equipped with weapons and riot gear, rigorously trained and they could have handled any riot. During the afternoon he and his men heard a commotion near the Youthful Offenders Block where the surviving prisoners were housed. This was also close to the entrance where they were. It was at this point, Seneviratne says, that he contacted the Operations Room at Army HQ by the direct radio link. This was about 20 minutes before the actual attack began (roughly 4.00 PM). He spoke to the junior duty officer whom he asked for permission to go into the prison and deal with the attack. The junior duty officer gave him a telephone number at Army HQ and asked him to speak to the senior duty officer (rank of colonel).

Seneviratne believes that he was the first to communicate the impending attack to Army HQ, from whence Jansz was then on his way back to the Prison Commissioner’s office. Curfew was declared at 4.00 PM. Jansz was told about the riot about 4.15 PM and he immediately phoned Brigadier Madawala at Army HQ, who as arranged earlier had agreed to keep a squad in readiness in case of attack.

Lt. Seneviratne went to the public call box inside the entrance and in the tunnel. Using coins collected from his men and the Chief Jailor who was at the entrance, he phoned the number giver by the junior duty officer and got hold of the duty officer who was in the Army Commander’s room at HQ. The duty officer told him that they were aware of the riot and were sending a back up team and asked him to stay out. Seneviratne asked to speak to the Army Commander. The duty officer told him that the President was also there and he could not speak to the Army Commander and insisted that he stick to the standing orders, failing which he would be court-martialled. The standing orders were not to go in to the jail at any cost, but to protect the jail from outside attacks only. The orders had nothing to say on the protection of prisoners.

Seneviratne told us that during this time he was in the tunnel with some of his men. They were able to move in and out through the small door attached to the big door in front. The second door with a metallic grill leading into the prison compound was closed but not locked. Jail staff were moving in and out of it into the tunnel. Some of his men who were with him fired at the attackers through the grill. Others had used an army truck and climbed onto the prison wall and fired from there.

The account in Arrogance of Power reflected the general perception that both prison attacks had been planned for just after curfew to prevent other prisoners escaping. There may also be another factor in the second. Arrogance of Power which also used Suriya Wickremasinghe’s analysis of the case, expressed surprise that neither the inquest proceedings nor the recorded testimony of prison staff made any reference to the whereabouts or role of Superintendent Leo de Silva or either of his two ASPs. It wondered if Leo was on the premises.

His son Lalanath said, “My father was in and out of that jail all through this time.

I was at home and he spent most of his time, morning, noon and night in that jail. That was not just during this period but that was his commitment to duty – The Prison Ordinance says that Prison officers are on duty 24 hours – he took that literally! He would say to me “Prisoners come and Prisoners go, but I am in jail forever”!

“The second massacre took place minutes after my father had come home to get a late

lunch and a quick wash – he had spent the whole night in jail and pretty much the whole morning and noon. He had barely come home (our home is the big house to the left of Welikade gate) when he heard shouting from inside the jail, the alarm siren etc and he ran back to the jail. Perhaps they all waited for him to leave? The timing was incredibly too perfect. My father did tell me that on the second massacre he was pleading with the army to fire tear gas – and that it took him many appeals and even some shouting to get them activated!”

The back up team sent by Army HQ comprised a group of commandos under Major Sunil Peiris. He and his men came through the small door into the tunnel. Peiris inquired about the situation from Seneviratne briefly before rushing in. By the time the commandos took control the attackers had enough time to kill 16 of the 28 prisoners locked up in the cells on the ground floor of the YO Block and Dr. Rajasundaram upstairs. Another died later in Hospital, bringing the total to 18.

Major Peiris in testimony given to us said that fire from his weapon injured a prisoner whom he saw being carried away. Lt. Seneviratne told us that his men too had fired at the attackers from the gate and some were injured. These facts were not recorded by Magistrate Wijewardene who also conducted the inquest into the second massacre at the request of Mervyn Wijesinghe. Nor was any attempt made to identify the attackers whom, as Suriya Wickremasinghe who interviewed survivors noted, could have been identified by them, as they fought off several of them at close quarters. Many survivors told her that they could have identified some of the attackers if seen again. After asking the survivors whether they could identify the attackers, to which the answer was no, since the prisoners did not know the attackers by name, the Magistrate failed to follow up with, whether they could identify the attackers if they saw them again (for example at an identification parade). It was also remarkable that whereas the prison staff, who at the inquest identified with ease the mutilated bodies of the victims, invariably said that they were unable to identify a single of the convicted prisoners who took part in the riot!

Lt. Seneviratne Barred from the Inquest

The presence of underworld elements imported into the prison for the second attack, which Lt. Seneviratne spoke of, had been rumoured for a long time and strenuously denied by senior staff in the Prisons Dept. Also rumoured before and denied by Prisons staff is a hole reportedly made in the prison wall after the second massacre. Lt. Seneviratne said that after Major Peiris arrived, his men alerted him to a hole having been made in the prison wall by the cricket grounds. He said that he personally saw it about 5.00 PM and an Air Force truck was parked opposite the hole, with an air officer present. He did not make an issue of it but simply looked at it and left. He believes this was how the injured prisoners and the underworld elements brought in were taken out, adding that there is a path there that leads to Borella.

Lt. Seneviratne told us that following the massacre AG’s Dept men and men from the Army’s legal department. came to Welikade prison to discuss the inquest. The standing orders and the logbook in which the soldiers logged in the vehicles entering were removed. He said a group of about 20 of them wanted him to tell the inquest that there had been a jailbreak attempt by detainees. He was placed under enormous pressure, but he refused to testify that he was outside the prison controlling a jailbreak.

Seneviratne felt very bad about not being allowed to go into prison and rescue the PTA detainees. He told the others that they refused him permission to go in and rescue the prisoners, but now they wanted him to make some false testimony. He said that he would only speak the truth and say that what happened was sheer murder.

The AG’s dept. men told the army officers present to convince ‘your man’. When he refused repeated pleas to give in, Major Sunil Peiris stepped in and told the others not to harass him and if he won’t, he won’t. Peiris said that if they wanted someone from the Army to testify, he would. Seneviratne told us that he had trained with the commandos and during that time he had become friends with Major Peiris.

Peiris testified at the inquest the following day, but he did not give substance to any attempted jailbreak. He answered what must have been a leading question with, “I did not notice any prisoners attempting to break out… I initially gathered that the mass scale jail break had been contained…”

Seneviratne was hoping that as the officer in charge at the prison, he would be called upon to testify as Lt. Hathurusinghe had previously been, so that he could place the truth on record. But he was not. Major Peiris was presented as the spokesman for the Army’s role and the part played by those on duty outside the jail was ignored. Suriya Wickremasinghe with whom Lt. Seneviratne first made contact adds, “In fact even those who later studied the subject carefully overlooked this omission, or assumed that the army unit outside had been unable or unwilling to do anything as during the first massacre.”

After the awkwardness with Leo de Silva at the first inquest, the AG’s Dept. was very choosy about witnesses. Leo de Silva and his two deputies were not called. The Chief Jailor, fourth in order of seniority, was brought in as though he were in charge. Explaining his position, Chief Jailor Karunaratne said, “Up to this point… to the best of my recollection there were no officers superior to me in office in the compound…” Indeed, Leo had gone for a quick lunch, but had come as soon as the alarm was raised.

It is now easy to see that the combination of officials and lawyers from the Army’s legal unit and the AG’s Dept., along with a willing magistrate, had scripted the inquest proceedings. Having kept Seneviratne out of the inquest, Chief Jailor Karunaratne was given a story to explain why an army unit had to come all the way from HQ when Lt. Seneviratne who was on the spot was not utilised. Karunaratne said: “I was also informed that some… prisoners in the remand prison had obtained possession of fire arms. I am now aware that in view of that situation some of the army personnel placed outside Welikade Prison had to go to the remand section to combat that situation.”

What Karunaratne could not say is that he was at the gate asking help from Lt. Seneviratne’s unit and gave him coins to call Army HQ to get permission, which was refused. He was thus scripted to explain the army unit’s absence with a fictitious riot at the remand section. He rather weakly explained the steps he took to prevent a mass jailbreak, sending his men everywhere except to the scene of attack.

Having failed to substantiate any jailbreak attempt, Magistrate Wijewardene still went undeterred to the scripted conclusion: “Both the army personnel and the prison officers had been hindered in the full utilisation of their forces to protect the victims of the attack by the intended mass jailbreak…However, prompt and efficient steps taken by the special unit of the Army under witness Major Peiris had effectively prevented the jail break referred to.” Major Peiris had been clear that there was no attempted jailbreak.

Post massacre fortunes of SP Leo de Silva and Lt. Nuvolari Seneviratne

Despite their large difference in age and having been in two different services, they had something in common. They instinctively respected the spirit of the law and found murder galling. During the fateful 48 hours at Welikade, which scarred their lives and virtually ended their careers, they moved in close proximity of each other, but perhaps never met. If they did, Leo would have been deeply distrustful of Nuvolari.

Leo’s son Lalanath said, “My father was convinced beyond a shadow of doubt that the Army set the prisoners up. Keep in mind this was a response to 13 soldiers being killed in the North by the LTTE. Here was a way to kill “LTTE” personnel right in Colombo. My father believed that by commissions (rousing prisoners to revolt) and omissions (refusing to cooperate to quell the riot and blocking emergency treatment for injured Tamil detenues after the first massacre) the Army was vicariously responsible for the events.”

Leo, as he confided to his family, continued in fear of grievous harm from the army units guarding the prison . He took the precaution of swearing an affidavit before his son, an all-island JP. He would leave the truth on record in a situation where the courts found no place for it. After all that happened and the position he took trying to save the lives of injured Tamil detainees and the court scenes where he protested to a rude and angry magistrate that he would speak the whole truth, a further incident related by his son enhanced his fear:

“After the massacres, he was walking to the jail from home once after dark, when he was challenged by an army officer. Upon giving his name and rank, the officer verbally signalled him to pass, but continued to point the gun at my father. Under normal practice the gun is lowered once permission to pass is given. My dad was angry at this insult. He went up to the officer and reminded him that he (my father) was of the rank of a colonel in the army and the correct thing was for him to lower his gun and salute him. The officer did not salute him but did lower the gun and stand to attention.”

In the affidavit, he affirmed his belief that the army personnel stationed outside the prison were instrumental in encouraging prisoners to attack Tamil PTA detainees. According to his son, “It was very clear to my father that during the first massacre, prisoners appeared confident that the Army would not intervene and that the Prison guards themselves neither had tear gas nor other effective means for mass crowd control.”

As the head of the prison, Leo de Silva felt it incumbent upon him to carry out an internal inquiry and identify the culprits responsible. In this he was thwarted by an order from the Commissioner of Prisons, Mr. Delgoda. He was a marked man given that the Government was determined to cover up the Welikade massacres. Leo de Silva was obstructed and finally pushed out at the age of 56. The prisons come under the Ministry of Justice, and Dr. Nissanka Wijeratne, who was then Minister for Justice refused him the extension of service that is routinely given annually after the age of 55. He was denied his pension and promotion as well. As a young lawyer, Lalanath had to file a fundamental rights case for him – and it was in a settlement they got there that his full pension was restored and his back wages were given on the basis of a promotion.

For Leo it was towards the end of his exemplary career, and being thrown out in that manner is a bitter pill for anyone. For Nuvolari Seneviratne, it was but the beginning of his career. He was then only 22 years old. He soon realised that by refusing to play along at the inquest according to the script, he angered many in the Army. Relations between him and his commanding officer Major (later Colonel) Jayantha Jayasinghe plummeted. The latter found himself blamed for not being able to get his subordinate to go along with their story.

Seneviratne and his men felt frustrated and unhappy that they had been prevented from going into the jail and rescuing the prisoners under attack. To many this would seem a very unusual attitude after what people saw from the Army at that time and especially from Lt. Hathurusinghe’s unit that was at the prison during the first massacre. Hathurusinghe was also in touch with Army HQ, but his unit went into the prison and were spectators to the massacre and also, later, prevented the injured from being taken to Hospital.

Generalisations could frequently be unjust. There were many soldiers, including from the ranks, who thought professionally, like in the case cited below. When the officer wanted a soldier to assault a prisoner, the soldier replied that an order asking him to shoot was one he was bound to obey, but not one to assault a prisoner. When a platoon works and trains together, a rapport develops and when the commander sees a task as a challenge to their professionalism, the men are bound to fall in line.

In this instance Seneviratne and his men saw it as their duty to rescue the prisoners. And their frustration must have increased when after a crucial delay, Major Sunil Peiris was sent in to do the very job they were both trained and eager to do and could have accomplished expeditiously. Where the public was concerned, Seneviratne and his platoon were cast in a poor light and left there for reasons of state. It appears that Army HQ was taken aback when Seneviratne asked for permission to go into the prison and do his job. They strictly ordered him to keep out of the jail, unlike they did with Hathurusinghe and his men, who were allowed in on a sight-seeing expedition.

Seneviratne says that three years after the massacre, knowing that there was no future for him in the Army, he put in his papers. He was refused and by this time the talk among several officers was that it was better to keep him in the Army, rather than let him go out and talk. He kept on putting in his papers to leave the Army. His promotions were also stalled, but he was posted to the battle zones in the North. Some called him a Tiger, claiming that those killed at Welikade were all Tigers. (In fact an overwhelming majority of those killed did not belong to the LTTE, but Tigers had become a generic name for Tamil militants.) Seneviratne argued that many of those like Rajasundaram were in fact intellectuals.

Finally, Seneviratne says, General Kobbekaduwa in 1992, understanding his position was sympathetic and signed his release. But just afterwards, in August 1992, he was killed and Seneviratne’s release was withdrawn. At this time Seneviratne, who by then held the rank of captain, was in Weli Oya. Whenever he was with his commanding officer Jayantha Jayasinghe, tempers tended to flare up and sometimes they almost came to blows. The area was one where there was constant LTTE infiltration and Seneviratne felt that he was being sent on missions from which he was not expected to come back alive.

At one point Colonel Jayasinghe had his salary stopped although he continued on active duty for a further seven months. When he went home on leave, Jayasinghe sent a message telling him not to come back. Without making a further issue of it, Seneviratne simply went away. It was in the year 2000 that he appealed to the Army Commander for a review to regularise his discharge from the Army. An inquiry was held, where some of his former brother officers supported him. The Commander regularised his departure and called for the payment of his arrears. Seneviratne says he was told unofficially to forget his back pay as the termination of his pay was improper and touching the matter would involve the Army in legal controversy.

The Standing of Seneviratne’s Testimony

A striking remark made by Seneviratne in the course of our conversations is that he would not be speaking out now, had he not seen the account of the prison massacres in Arrogance of Power, which concluded that there was no attempted jailbreak during the second massacre, contrary to what the Magistrate maintained. For, Seneviratne said, “No one would have believed me”.

One would soon realise that his fears were very real. Senior Prison Department staff have maintained over the years that there was no presence of outsiders during the second massacre and they dismiss the claim that a hole was made in the wall. The infirmity in their denials is that a proper inquiry was never held and the culprits were not held to account. And after the kind of disaster that occurred, one would have expected some open accounting. On the other hand Commissioner Delgoda blocked Leo de Silva’s attempt to hold an inquiry and he alone appears to have paid dearly for his independence.

On the other hand Leo de Silva’s assessment has been that the Army was mainly to blame. His son told us, “I recall (and I said so to the Truth Commission) an army truck with soldiers cheering “Jayaweva” (Victory) speeding around the perimeter road of the jail even as the massacre was happening (I cannot remember if it was the first or second). I saw this myself through the rear window of our house – where my sister, mother and aunt were and prisoners could have heard this as well.” This incident we believe took place after the first massacre. Seneviratne vigorously denies that this happened on his watch.

The first day of widespread communal violence, July 25th, was soon after the killing of 13 soldiers in an LTTE mine attack in Jaffna. Besides, Leo de Silva’s personal experience with the Army too would have strengthened his assessment of the Army being the main instigators with tacit government support. However, the evidence we advanced in Sri Arrogance of Power points to both the communal violence and even the prison massacres having been planned well in advance.

The countdown in July, the President’s Daily Telegraph interview on fighting terrorism without impediments of the law and the orchestrated belligerence were pointers to the coming menace. Leo de Silva had even before the massacres called for the Tamil prisoners to be transferred, having sensed something nasty in the offing.

Evidence that Lt. Nuvolari Seneviratne was indeed a conscientious objector to what his superiors wanted him to do, is the fact of the AG’s Dept. shunning his testimony. Arrogance of Power had found this remarkable and in need of explanation.

We found Lt. Seneviratne’s evidence eminently credible, not jarring anywhere, but adding to our understanding of events. His answers to questions regarding difficult points in his testimony came across convincingly without hesitation. A second massacre had been anticipated. Acting Commissioner Jansz wanted the transfer of prisoners expedited. The President and the Army Commander knew the gravity of the situation at the prison. Whether or not Seneviratne’s advance warning to the junior duty officer was communicated to them, they sent a back up team after Jansz communicated with them. One finds it strange for an army that the junior duty officer should have asked Lt. Seneviratne to go to a public call box and phone the senior duty officer in the same HQ premises.

While the army unit at the entrance had been kept idle, the Magistrate was anxious to conclude that there had been an attempted jailbreak. Seneviratne affirms that his pleas to go to the aid of the prisoners were turned down and he was asked to do nothing and pretend that there was an attempted jailbreak, so giving the attackers more time. All this makes perfect sense if the Army HQ had connived in the crime. If not Seneviratne could simply have been ordered to go in.

We come to the controversial elements of his testimony. One is about outsiders getting into the prison since the morning in official vehicles and the hole in the wall. Lalanath de Silva who shares the skepticism of senior prison officials at that time, says of outsiders getting in, “It is also highly unlikely that this could have happened under my father’s nose. He was an extremely alert man and was fully conscious of this possibility. Whether this happened when my father was not in the jail, I don’t know.” He suggested that blaming goons and thugs from the outside might suit the Army to deflect the searchlight from themselves. It is however well to remember that in the situation prevailing after the first massacre, Leo de Silva’s authority had been grievously undermined.

A strong indication of political machinations in the second massacre that Arrogance of Power has drawn attention to is a cabinet meeting that same (27th July 1983) morning reported in Sinha Ratnatunga’s ‘Politics of Terrorism: The Sri Lankan Experience’. The question of transferring the survivors of the first massacre out of Colombo to Jaffna prison had been raised. The author, who wrote the Migara column in the Weekend and was reputed for excellent inside contacts with President Jayewardene’s circle, reported that Ministers Lalith Athulathmudali and Ranil Wickremasinghe objected to the suggestion on the grounds that it would ‘further infuriate’ the Sinhalese. From what Lt. Seneviratne’s men told him, it would appear that even as these words were being uttered, underworld elements were being inducted into the prison in official vehicles.

We contacted S. Manoranjan editor of the Lake House Tamil monthly Amuthu from 1999 to 2001. In July 2000 Amuthu published an investigative report on the Welikade prison massacre. It said that a group of underworld figures led by Gonawela Sunil, a UNP thug from Kelaniya, had been brought into the prison to lead the second massacre.

Manoranjan told us that there were three journalists working on this piece. They had approached Mr. Ganeshalingam, a long time UNP stalwart in Colombo and subsequently mayor of Colombo, for help. He directed them to a former member of the UNP trade union JSS which earned notoriety at the time of the communal violence under the leadership of Minister Cyril Mathew, also MP for Kelaniya. It was this former JSS member who told them that goons from Kelaniya under Gonawela Sunil were brought into Welikade Prison to carry out the second prison massacre. This story had been in the rumour mill for a long time.

We may also note that at some level there was apparently unhappiness with leaving the Welikade Massacres case to rest with merely the highly publicised inquest reports of Magistrate Keerthi Wijewardene as the last word. Or perhaps this was simply the result of the internationally expressed outrage. The Appendix gives the copy of a letter provided to us by the Civil Rights Movement where A.R.B. Amarasinghe, who had by early 1984 succeeded Mervyn Wijesinghe as Secretary/Justice, requests the Chief Justice to nominate a judge of the Supeme Court to inquire into matters pertaining to the massacre. One question notably concerned the possible presence of outsiders who were neither prisoners nor prison officials.

The attempt to hold an inquiry did not get off the ground. The reasons must for the moment remain a matter of speculation. It does however tell us that the possibility of an unauthorised presence of outsiders was taken seriously in the aftermath of the massacres.

Seneviratne’s support for this charge of the involvement of outsiders in the second massacre comes totally independent of any other report and without frills. He did not know about the affiliations of the underworld figures, but reported the mere fact of what his men learnt from the jail guards they worked with. His report of the hole in the wall had also been previously rumoured and adds nothing to his verifiable and damning testimony about the massacre itself.

Other Dissidents in the Saga of Welikade Prisoners

Cases of other dissidents who come out with credit in the story of the PTA prisoners were given to us by Suriya Wickremasinghe. She was told of these during her extensive interviews with survivors and we give them as related by her:

– The jail guard who successfully stood guard at the entrance to one of the wings in the Chapel building during the first massacre, blocking the doorway with his arms and legs spread out so that he formed an X. (Recounted to me by one of the survivors, who demonstrated how the guard had stood). Other survivors spoke of a jail guard, presumably the same one, who put his foot on the lock of the entrance to the corridor and said if you break this you have to cut my foot. It is correct that one of the wings housing Tamil prisoners in the Chapel Building was not broken into at all during the first massacre and all its inmates were thereby saved.

– Even more significant, the soldier in army camp (Panagoda if I recall right) before the prisoners were transferred to Welikade, who told his superior, when refusing to assault a prisoner, that he can order him to shoot, but that he cannot order him to beat a prisoner.

– Another survivor spoke very emotionally of a prison officer who was kind to them in Welikade and wanted me to convey to him his good wishes! This same survivor told me that if he ever sees again those who tortured him, he just has to kill them. This tale of regular assaults in army custody was a feature of almost all the testimonies, and they were very relieved when they were transferred to Welikade, where life was a comparative paradise until the 25th of July 1983. When interviewing these survivors, I was always in a hurry to hear about the massacres, but invariably first let them get off their chest the account of what they had undergone up to then. It was also a standard feature that admiration at times indeed amounting to love for those who treated them humanely was as strongly expressed as hatred for those who did the opposite.

The Question of Premeditation in the Massacres

We mentioned earlier that to most of us who in 1983 were politically alive as Tamils, and to the community having been placed at the cross roads by the infamous events, nothing we read or heard ever caused us to doubt that both the prison massacres were planned and executed by elements in the government of the day. It happened after the Tamil PTA detainees had been transferred from military custody and other prisons to Welikade prison.

Premeditation is hard to prove as no proper investigation was conducted and some of the key witnesses have since died. Many would still argue after extensive research that the transfer of prisoners to fiscal custody had been demanded by the main Tamil parliamentary party, the TULF, because of complaints of assault and ill-treatment in army-custody. The first massacre could also be explained as a result of purely local instigation in response to the upsurge of anti-Tamil emotions outside, granting that some jailors (persons of officer rank in the prison service) were also involved.

Many of these questions were dealt with in Arrogance of Power. We summarise the essential points and add a few more. Arrogance of Power could not have been written, but for an exceptionally conducive environment prevailing under the early years of Chandrika Kumaratunge’s presidency. There was a war and there were serious ongoing abuses, but for all her shortcomings as a leader, she stated unequivocally that there was an ethnic problem and genuine political grievances among the Tamils that needed a federal settlement. She repeatedly spoke of July 1983 as an outrage that needed to be come to terms with. One cannot readily see that her appointment of a ‘Truth’ Commission to go into the events of July 1983 was calculated to derive political mileage. Given the quagmire into which local politics had entered, her position as a leader was a major step for this country, as seen by the ease with which her successor has slipped back into primordial Sinhalese nationalism, leading to much uncertainty.

The atmosphere prevailing in the latter 1990s gave unprecedented access to material and to serving and retired officers in the security services, who believed that the ethnic problem had been badly mishandled and were willing to talk frankly about their experiences. An especially important group of contacts was journalists who had been active during the mid-1980s and had informally hobnobbed with key ministers.

Not only were a number of them convinced that the a section of the government was behind the prison massacres, but also that Jailor Rogers Jayasekere was the key linkman. Senior members of the Prison Dept. confirmed this to us obliquely. The journalists knew Jayasekere, whose father had worked for President Jayewardene when he contested Kelaniya earlier in his political career, as a UNP hatchet man, who provided behind the scenes support when the party wanted to play rough. In the prison he was polite and English speaking but his party affiliations to the UNP – the ruling party then – were also well known.

Citing Gamini Dissanayake, a leading minister who was then being overtaken in importance by National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali, a leading journalist told us about Jayasekere’s involvement in establishing Sinhalese settlements in Tamil areas – Weli Oya in this instance. Jayasekere, he learnt was picked for the job of arranging for selected Sinhalese prisoners in Anuradhapura prison to be moved to Manal Aru in Mullaitivu (Weli Oya in Sinhalese) to pioneer a Sinhalese settlement. (This first group sent by Jayasekere was massacred by the LTTE in November 1984.)

Given Jayasekere’s background, it was eminently credible that the Welikade massacre was entrusted to him by leading members of the Government. Former detainees named two other prison officers who played a leading role in the massacres. They are Jailor Samitha (Rathgama) and Location Officer Palitha. There were also other reasons that added weight to the contention of premeditation.

A former prisoner in Welikade, now living abroad, told us that their being moved to Welikade had nothing to do with the request by the TULF. He said the TULF request was made 1½ years earlier and the prisoners themselves launched a hunger strike several months before to press this demand. This prisoner was moved to Welikade from Panagoda Army Camp as part of the movement to Welikade, which began on 3rd June 1983 and ended 11 days later on the 14th. The context of this movement was also the Public Security Ordinance, which was brought into force on the same day the movement began – 3rd. The former prisoner was among four who were released around 9th June. He believes they were released because there was nothing against them. Looking back he feels quite certain that the fate of the rest was already sealed. He points to the following, which seem to him significant in retrospect:

- Of the 72 Tamil PTA or ER detainees concerned in the massacre drama, 63 were concentrated in one place – in three wings on the ground floor of the Chapel Section – irrespective of status. Some had been convicted, some had court hearings in progress and there were those against whom charges had not even been formulated or whose offences, if any, were not even of a criminal nature and should have been released. [The remaining nine prisoners of standing were held at the Y.O. Block to which the survivors from the first massacre were then moved. There were also Tamil suspects held in other parts of the prison.]

- During the same period some criminal elements were moved from other prisons to the Chapel Section. Among them were Sepala Ekanayake and Akuna Santhre (Hemachandra) who were in Magazine Prison. The first took a prominent role in the second massacre and the second was a notorious killer.

This former prisoner suggested that A. Varadarajaperumal who was in Magazine Prison might have more information on this. At our request Mr. Varadarajaperumal sent us some notes. From his testimony, we gather no evidence that any prisoners were moved to the Chapel Section in preparation for the massacre. Akuna Santhre remained at Magazine. Sepala Ekanayake was transferred to the Chapel Section. His trial for hijacking commenced on 30th June 1983.

Varadarajaperumal was interrogated by an ASP from the CID on the 4th Floor around 1st April 1983. This police officer kicked him onto the ground, screamed at him that one day Bambalapitiya and Wellawatte (Colombo suburbs with a large Tamil population) will burn, as happened the coming July, and kicked him again.

Concerning Sepala Ekanayake, Varadarajaperumal said that at Magazine he used to be notably uncommunicative with Tamil prisoners and was also known to express strong anti-Tamil views among other prisoners. This was in marked contrast to his disposition towards the Tamil prisoners at the Chapel Section, where he cultivated a cordiality that was about excessive – greetings in Tamil and expressions of solidarity with their cause. Several Tamil survivors of the massacres refused to believe that he played a leading role in the second massacre. It is quite possible that those planning the massacre in the Chapel Section had recruited him and he was enjoying the deception of bogus cordiality with the intended victims. Appendix II gives a translated extract from Varadarajaperumal’s notes.

More pertinently, it must be remembered that the transfer to fiscal custody coincided with putting the PSO into effect with talk of getting tough on terrorism. Barely three weeks earlier, in May, sections of the Government had had unleashed communal violence against Tamil students at Peradeniya University (Supplement to Special Report No.19 Part-I).

On 12th June 1983, just as the movement of prisoners to Welikade was being completed, a report in the Island revealed that some in the Government were obsessed with these prisoners and proposed changes to the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Criminal Procedure Code giving the Army as part of routine law powers they already had under the PSO and various Emergency Regulations. The proposed amendments empowered the army personnel to use lethal force in respect of ‘terrorist suspects attempting to break jail or making a bid for freedom’. In the event of a suspect’s death, the only legal obligation was to make a report to the Attorney General’s Dept. on the circumstances of the death. This was the thinking reflected in the standing orders given to the army unit posted outside the prison.

A strong piece of evidence of premeditation comes from the fact that the communal violence of July 1983 was meticulously planned with the collection of electoral lists and assignment of UNP hit men to areas, behind the rhetoric of dispensing with the law to defeat terrorism. The attention the Government devoted to the PTA detainees in the run up to the violence (which was largely independent of the incident in Jaffna where 13 soldiers were killed) would make it highly remarkable if they were left out of the planning. The behavior of the army hierarchy during both massacres when the President was at Army HQ and the termination of the services of Superintendent Leo de Silva after he tried to hold an internal inquiry are further pointers.

The Curse of a Generation

To SP de Silva, Lt. Seneviratne and their families, it has been many years of pain living under a cloud of suspicion for crimes they tried to prevent, their honour tarnished. For the country itself it has been a steady erosion of values for a generation, taking a heavy toll on the honest and honourable. In the journey in time from Welikade to Mutur and Pottuvil, we have seen a host of crimes that would have been easily dealt with if our Courts, the Police and the AG’s Dept. were geared to bringing out the truth. With obfuscation having become the norm for these institutions, those committed to the truth need to go through a painful process of trial and error.

A more perfect account needs to stand on the shoulders of imperfect accounts. But the sanity of a society demands that the truth must be placed on record and those guilty understand the feelings of the others. Imperfect accounts have their place. It is through them that others feel motivated to respond and improve the stock of information.

For a generation we have been locked into a regime of crimes and counter-crimes. While those of governments may come to light, many years later perhaps, through conscientious objectors, such persons stand no chance in Tamil society. Crimes of the LTTE are far more likely to come to light in psychiatric clinics. Placing the truth on record has a necessary curative purpose, so that if not we in our time, another generation could at least see the light of dawn.

Acknowledgement: The Welikade Prison Massacre remains a live issue largely because of the Civil Rights Movement and Suriya Wickremasinghe. They have been the chief repositories of its memory and we hope Suriya’s book on the events would be published before long. The reader would see that much of the information contained here and what appeared in Sri Lanka: The Arrogance of Power…owed critically to resources provided by her and CRM. Her editorial suggestions to this account were such as to help it stay within the bounds of evidence as against extrapolations and what we have taken for granted. We might add that she holds reservations about some of our conclusions. On a further note, Nuvolari Seneviratne who was at the time of the massacre a lieutenant in the Sri Lankan Army made contact with Suriya Wickremasinghe after seeing the account of the massacre in Sri Lanka: The Arrogance of Power… on our web site. We invite readers to send any further information to us at [email protected]. This would be passed on to Suriya Wickremasinghe.

Appendix I

Letter from Secretary, Justice, Amarasinghe to Chief Justice Samarakoon

3rd January 1984.

The Hon. N.D.M. Samarakoon, Q.C.,

Chief Justice,

Chief Justice’s Chambers, Hulftsdorp,

Colombo 12.

Dear Chief Justice,

Welikada Incidents

Further to our discussion this morning, I shall be grateful if you would assist us by nominating a Judge of the Supreme Court to investigate and report to the Hon. Minister of Justice on or before March 15th 1984 on the following matters:

1. What were the significant and relevant incidents leading to the deaths of certain persons at Welikade Prison on 25th and 27th July 1983?

2. What were the significant and relevant incidents and events which took place at Welikade Prison on the 25th and 27th July 1983?

3. What were the significant and relevant incidents and events after the 25th and 27th July 1983?

4. Did the prison authorities sufficiently discharge their duties and if not, who were the officers to blame and in what way?

5. Were the physical facilities and security arrangements adequate, if not, in what way were they deficient?

6. At the time of the incidents in question, were there any persons within the prison who were neither prisoners nor prison officials? If so –

(a) who were they?

(b) how did they gain admission?

(c) Were they armed and of so, in what way?

(d) were they directly or indirectly responsible for the incident in question and if so, in what way?

7. What steps if any, should be taken to prevent the recurrence of such incidents?

Yours sincerely,

Dr. A.R.B. Amarasinghe

Secretary,

Ministry of Justice.

Appendix II

A Note from A. Varadarajaperumal

Annamalai Varadarajaperumal (Varathar), along with Maheswararajah, an MA student at Jaffna University, and 10 other members of the EPRLF were arrested by the Police in Batticaloa on 31stMarch 1983, at what was essentially a political meeting. What the Police found were innocuous political materials. They were all imprisoned in Magazine Prison, Colombo, under the PTA and their detention was prolonged by the CID periodically reporting to the Magistrate that there was a delay in obtaining translations of their materials. Varathar was in Magazine prison nearby when the massacres took place in Welikade. Some of his experiences are described below:

Four days after our arrest we were taken to Magazine Prison. Maheshwararaja and I were kept in solitary confinement. A little later we were joined by Vamadevan from KKS, who was S.J.V.Chelvanayakam’s driver. I came to know him during the famous 1975 parliamentary by-election in KKS. He was arrested in Batticaloa in connection with the Chenkalady bank robbery in which he was involved with Paramadeva. Having been in prison long, he knew the other prisoners and the prison officials, whom he introduced to me. There were near us two prisoners held in maximum security conditions. They were Akkuna Santhre (Hemachandra) and a Muslim who was involved in several robberies in Maradana. Also held with us was Thanga Mahendran, a founder member of TELO in 1975.

The hijacker Sepala Ekanayake was separated from us by a tin fence. He hardly ever spoke to the Tamil detainees. A few days before the July 83 incidents a rich Tamil from Colombo was brought there in connection with foreign exchange fraud. It was he who gave us much information about Sepala and said that he used to vomit communal venom among the Sinhalese detainees.

It was customary for the prison superintendent to meet us on our first or second day in prison. When it was my turn to see the SP, I was in for a shock. He was Ratnayake, the Chief Jailer when I was imprisoned in Welikade H ward during 1975 to 1977. We then knew him as an arch Sinhalese communalist. But this time he struck me as a decent man. My impression was that there had been a genuine change.

I could sense that the events of July 1983 were planned and unleashed on the Tamil people and, by early April, plans were already known in intelligence circles. Two days after my arrest, 1st or 2ndApril 1983, I was taken to a room of an ASP on the 4th flour of the CID building. When I answered his questions about the Tamil struggle, he instantly abused me in filthy language. From where he was seated on the table, he kicked me and I fell against a corner. He screamed at me that one day Bambalapitiya and Wellawatte will burn and kicked me again while I was on the ground.

In Magazine Prison there were Sinhalese communalists among the prison staff and also some very decent people. When the violence began on 24th July, one jail guard told me with deep feeling that this country has been pushed back 50 years. On the 25th when the first Welikade massacre took place, we were locked up earlier than usual. It was on the radio that we heard of what had happened. When we were let out the following morning, Vamadevan warned me that Akuna Santhre, who was friendly with us until that day, was gritting his teeth and looking at us with a twisted face. He told us not to talk to him. Communalism had got even into this veteran prisoner, notorious murderer, robber and social outcast. Sensing the situation was bad we asked SP Ratnayake to move us to where the other Tamil detainees were. A few hours later Maheshwararaja, Vamadevan and I were joined with the other Tamil political prisoners.

There was curfew on the 26th. No new restrictions were placed on the prisoners, but the prison officers were alert and maintained control of the prisoners.

On the 27th of July we were all suddenly locked up a short while after lunch. We were afraid that a massacre might be unleashed in our section. We requested a jail guard to allow us all in the lobby. This was refused and we were unable to contact the SP. When we were locked up in our cells in threes and fours in the evening, a jail guard who was a communalist searched the cells carefully and took away all objects that could be used in our defence. We heard the sounds coming from the Welikade during the 2nd massacre. About 10.30 or 11.00 PM, the doors were suddenly opened and senior prison officials came into the lobby. We were asked to collect our things. We were taken to the office and our properties were returned to us. It was like a dream. We didn’t know what was happening.

As we were being taken out Superintendent Ratnayake came to me and was visibly very upset. He apologised for what had happened to Tamil prisoners and added that we were being moved to a safe place. One prison official told me that there had also been plans to use Sinhalese prisoners in a similar massacre at Magazine prison on the 27th, and we should be grateful to SP Ratnayake for being alive up to this moment. We were taken to the office of the Commissioner in charge of Welikade and Magazine prisons. There were military vehicles around. I saw Deputy Commissioner H.G. Dharmadasa issuing instructions to prison officials. I knew him as the Superintendent of Bogamabara prison, Kandy, when I was there 10 days 1976. Tamil political prisoners who had spent several years there regarded him a gentleman. When I saw him I felt comforted.

Finally we were taken to Katunayake airport in a closed vehicle. We sweated and some among us urinated inside. It was hours before soldiers took us out one by one to urinate. We had been through an agonising time with much uncertainty. It was when finally the aircraft touched down in Batticaloa that we cried and hugged each other. We felt we had come home. I related this to H.W. Jayewardene at the 1985 Thimpu talks, when he would not accept the idea of a Tamil Homeland. I pointed out that they had themselves sent Tamil people to Batticaloa, Trincomalee and Jaffna after every instance of communal violence.

[1] http://www.uthr.org/Book/CHA10.htm#_Toc522197581

*University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna) Sri Lanka – Supplement to Special Report No.25 – Date of Release: 31st May 2007